Back for a second year in 2024, the Kings Festival of Artificial Intelligence has established itself as an essential event for anyone with an interest in AI. With public lectures, interactive displays and even a family zone, it makes the complex and pressing issues surrounding artificial intelligence accessible to all.

I went along to three fascinating talks covering a really broad range of topics, from the potential “dystopia on the doorstep” and what we can do to bring about the right kind of change instead, to historical concepts of general intelligence and their implications for AI, and the possibility, ethics and consequences of machine consciousness.

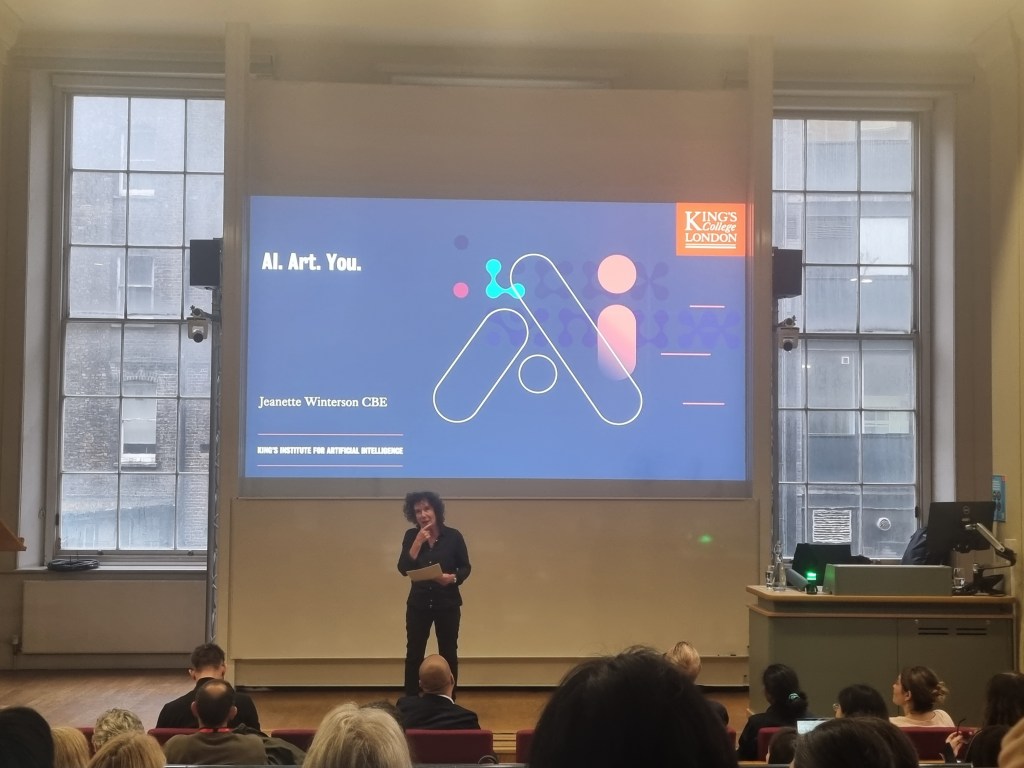

Jeanette Winterson: envisioning AI for the many, not the few

Human exceptionalism – the idea that we’re special or better than other beings – got us where we are. Now, in a world containing AI entities, we’re going to have to get over it. One of our great fears is that AI may not align with ‘human values’ – that it may have different priorities from ours. But since our values as a species have lead us to threaten the planet with extinction, would that be such a bad thing?

Jeanette Winterson’s wide-ranging talk was optimistic and inspiring: a call to arms urging us to envision a positive future with AI and make it happen. Focusing on human strengths like creativity and storytelling, Winterson showed us how ‘magical thinking’ has historically helped us to effect real change, going what is to what if. And she demonstrated how previous societal shifts, like the Industrial Revolution, could have marked real progress ‘for the many’ and not just those who would profit from it. Rather than adopting a fatalistic approach and leaving the future in the hands of the tech giants, it’s something for us to grab hold of and steer.

The concept of intelligence, in context

What do we understand by intelligence, and how is this influencing the development of AI? That was the question put by historian Dr David Brydan in his discussion of the cultural context surrounding the concept and meaning of intelligence through history. Dr Brydan’s lecture outlined the changes in the way we have thought about intelligence since the Enlightenment, and the social implications, such as control, colonialism and exclusion of particular groups, that have been enabled as a result.

We didn’t always think of intelligence as one unitary thing. Concepts like wit and wisdom were more widely used and offered slightly different meanings, suggesting a more nuanced appreciation of varied cognitive attributes. Over time though, the idea of intelligence (and its opposite, irrationality) became a way to class people as inferior so as to gain power over them. It was accepted that irrational colonial people couldn’t possibly take care of their own land, for example, so they needed guardians to do this for them. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the study of intelligence became more systematic. This ultimately led to study of neuroscience as we know it today (as well as taking some sinister turns through eugenics and the segregation of races in schools.)

What does all this mean for us, today? Well, it’s instructive to note how contingent our current ideas are on the narrow preoccupations of a particular point in time. The continued pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), for example – the ability of a single machine to learn, plan and execute a range of tasks rather than specialise in one particular area – has its roots in a relatively recent concept of generalised intelligence developed by Charles Spearman in 1904. Similarly, the quest to build an artificial brain was what led to the development of the first computers.

Could machines be conscious?

This is the type of question to which many people have an instinctive, yes/no answer. But that would make a pretty short lecture. In an engaging and accessible talk, Dr Sanjay Modgil, AI researcher and philosophy lecturer, made a short case to get us to accept the remote possibility of sentient machines, before going on to explore what this might mean.

It all comes down to general intelligence again. Dr Modgil asked us to consider what conscious awareness does for us humans as generally intelligent, adaptable beings; when it happens and why it might have evolved. The fascinating answer is that we actually spend a lot of our time in our own made-up reality, a ‘best guess’ generated by our brains based on what has come before, carrying out routine actions without conscious thought. But consciousness allows us to adapt to our circumstances, jolting us to our senses when things don’t happen as expected and helping us come up with creative ways to deal with new challenges.

So, if we are to try to develop an artificial general intelligence (rather than the narrow forms of AI we currently have), it’s somewhat likely that consciousness might emerge to enable this, just as it did with us. Especially if we consider that the way that AI has been incentivised to achieve its goals has been through a framework of rewards.

But imagine the ethical implications of conscious machines: we might have the power to copy/paste countless new beings capable of suffering into existence. Some, like Thomas Metzinger, see this potential as reason enough to halt the pursuit of AGI. Others don’t go this far, but are concerned about the moral conflict implied by bringing conscious entities into being only to treat them as slaves. More mindbendingly, it’s quite likely that intelligent but non-conscious AIs would figure out the best strategy for them to achieve what they ‘want’ might be to convince us humans that they are conscious – even though they are not. (And since we readily anthropomorphise our robot vacuum cleaners, that probably wouldn’t be very hard to achieve.)

Takeaways from the festival

The key theme running through these very distinct discussions was the importance of diverse perspectives, and interdisciplinary involvement, in the development and deployment of AI. Jeanette Winterson urged us to get involved and take back some of the power held by the tech giants, while David Brydan highlighted the importance of understanding historical context. Finally, Sanjay Modgil emphasised how anthropologists, psychologists and philosophers all have something to bring to the table when it comes to AI ethics.

Hosted by the Kings Institute for Artificial Intelligence at KCL, the Kings Festival of Artificial Intelligence actively promotes this interdisciplinary approach, with debates taking place this year on a variety of topics from healthcare and education to sustainability and social justice. I look forward to seeing what’s in store in 2025.

Leave a comment