DeepSeek purports to be opening up the “black box” in Generative AI. Whereas most current chatbots simply spit out a response to your question, DeepSeek’s DeepThink(R1) mode also shows its workings, providing the user with an explanatory “chain of thought” to demonstrate how it got there. But what does this really reveal, and is one explanation ever enough?

Why explanation is important: the black box problem in AI

At school, we’re taught that simply giving the right answer to a problem isn’t always sufficient. What our teachers and examiners are more interested in is our thought process. They want to see the reasoning we have used to come up with our answer, so that they can check we’re approaching the problem using an appropriate combination of learning and logic.

That kind of transparency is of value in all sorts of situations. We can ask a colleague to justify their decisions on a project, or request feedback from the recruiter when we don’t get chosen for a job. In our personal lives, open communication is essential if we are to feel close to others and build authentic relationships.

But when it comes to (most current) complex deep learning AI systems, we’re faced with something opaque. In the early days of AI, simple systems tended to function using explicit rules programmed by humans. These were relatively transparent because everyone had access to the logic being applied to decisions. Then, with the advent of machine learning – systems that learn for themselves from vast amounts of data rather than following specific rules – that transparency was lost. Today’s deep learning models are so complex, with vast training datasets, layer upon layer of artificial neural networks, and millions if not billions of internal parameters, that it’s almost impossible for us to dig down and understand exactly what takes place within.

The black box problem is more than just an intellectual issue for philosophers and engineers to puzzle over. It affects all of us on personal level, because without transparency we can’t detect bias, identify errors or ensure fairness in the technology that is increasingly governing our lives. When you consider that AI may be used, now or in the near future, to come to decisions about loan applications, medical diagnoses and criminal justice among other things, it’s easy to see just how high the stakes are. We can’t afford not to understand how these decisions come to be made.

What kind of explanation are we looking for?

There is ambiguity at play when we ask “Why?”. In From Bacteria to Bach and Back, Dennett illustrates this well, making a distinction between two types of “Why?” question.

- “How come?” is a question we ask when we want to know how or why a particular state of affairs has come to pass. We want some kind of causal explanation. It’s what we are asking when we enquire, “Why are the planets round?”

- “What for?” is a question in search of an intended purpose. We ask this when we are looking for a reason why a particular decision has been made, or why one choice has been selected over others. It’s what we’re getting at when we ask something like, “Why are ball bearings round?”

Further, as Dennett’s disambiguation seems to suggest, the difference between physics and the inner workings of the mind is pertinent when we seek to understand “why”. Discussing the world of cognitive science, Baron makes a similar distinction between psychological explanations (where we examine people’s beliefs and desires to gain insights in to why they have done something) and neuroscientific explanations (looking to the laws of biology and physics to understand the what happens in the brain when a particular action is taken).

In addition, we can make a contrast between general and specific explanations. General rules such as the laws of physics are all well and good when we want an abstract understanding of the way things usually happen, such as why the sun rises each morning, but in many cases we want specifics. When we are looking for insight into the particular parameters of an individual situation, generalistic explanations often feel unsatisfactory because we need the concrete details pertaining to that particular case.

Probabilistic explanations seem to fall into this generalist category. This type of explanation relies on a statistical overview of how likely something is to happen overall – so, if you toss a coin 100 times it’s likely that you’ll get heads about 50% of the time. The trouble is that probabilistic explanations don’t allow us to fully understand the particularities of a given event: why did my coin land heads-up on the thirteenth toss? Unfortunately, in fields like quantum physics where chance and randomness come into play, probabilistic explanations seem to be as far as we can go.

A final distinction to make when we ask “why?” is that between explanation and justification. Sometimes, when we have narrowed down the scope of our question to a psychological account of specific situation, it turns out that we are not so much seeking an explanation as looking for a justification of a person’s actions. When we demand “Explain yourself” in this context we’re not looking for causal facts; we want to be persuaded that the person’s choice in this case was the right one. This form of explanation is grounded in social context: its effectiveness depends on how well it makes its case to the questioner.

With all of this in mind, Miller lays out some desirable criteria for explanation in artificial intelligence:

- The explanation should contrast what actually happened with what could have happened in a counterfactual situation. It should address why this, and not that.

- It should be selective, just giving you the relevant pertinent information rather than listing all of the many contributing causal factors. (If I want to know why my toast is burnt, I don’t need to go into the mechanics of heat transfer – I just want to understand whether the toaster is burnt or on the wrong setting, for example).

- It needs to be pertinent to the actual way things turned out, rather than appealing to statistical likelihood – we want to know the real, actual explanation in this particular case rather than the probabilistic best explanation.

- Finally, it should exist as part of an interactive, two-way conversation, between the explainer and the explainee.

These criteria seem to be a good starting point in pinpointing the quality of explanation we are looking for from AI systems. But, as every toddler knows, it’s always possible to ask a further “Why?” question.

Turtles all the way down: When is an explanation sufficient?

My first reaction to DeepSeek’s chain-of-thought feature was, “That’s interesting. But now I want a chain-of-thought explanation that explains how it arrived at the chain of thought.” Am I letting myself in for an infinite regress with this way of thinking? (And would that be such a bad thing?) It’s a bit like the idea of the world resting on a giant turtle, which in turn rests on another turtle, and so on ad infinitum.

Perhaps this isn’t as “out there” as it might seem. Epistemic infinitists, for example, believe that when it comes to justifying knowledge, accepting a regress is the most rational way forward. While not ideal, the infinite regress is one of three rather undesirable options open to us when we consider how to justify a particular belief. We can:

- (a) Go back forever, looking for ever more reasons to justify our assertions (infinitism)

- (b) Start to go round in circles, with A justified by B justified by C which is justified by… A, because the important thing is not to get back to a foundational belief, but that all beliefs fit together (coherentism)

- (c) Have a stopping point somewhere, with an assertion that doesn’t need any further explanation (foundationalism)

There are problems with all of these options. Going round in circles feels philosophically unacceptable, but finding a foundational assertion that needs no further justification isn’t easy, and the stopping point could be seen as arbitrary. Considered in this context, an infinite regress could be seen as the most attractive horn of this trilemma. (It probably means, however, that in practice your beliefs can never be fully justified).

Is that what’s going on though, with my intuition that one explanation simply isn’t enough? Perhaps it’s just that the nature of the explanation you’re given is somehow unsatisfactory.

Enter DeepThink(R1) and Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental

I decided to put Deepseek’s DeepThink(R1) chain-of-thought mode to the test, alongside a competitor, Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental.

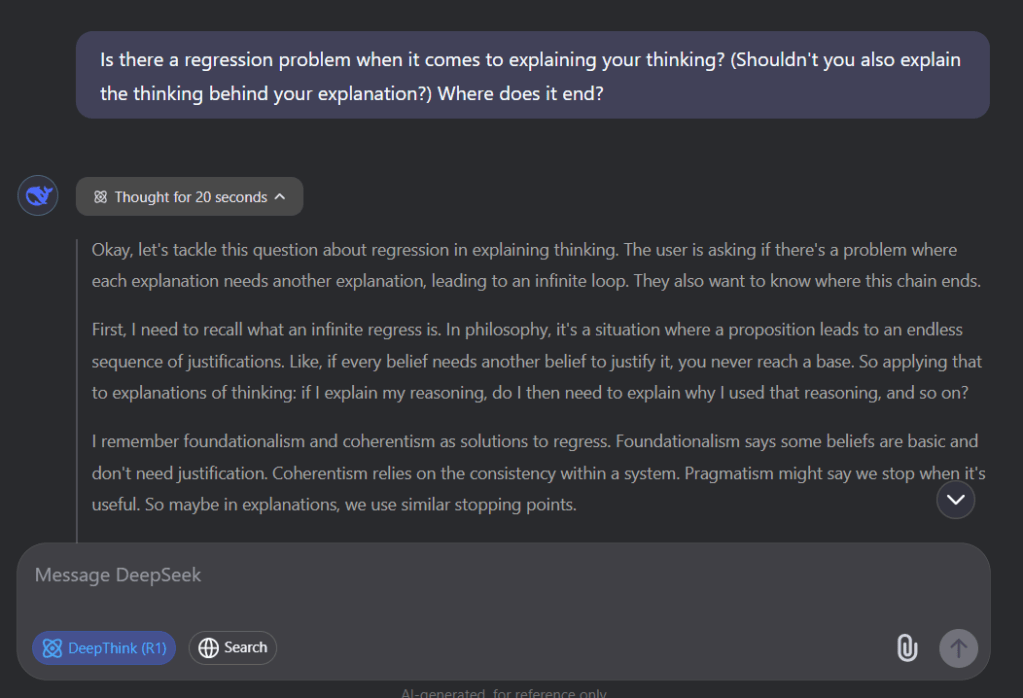

I asked DeepSeek: “Is there a regression problem when it comes to explaining your thinking? (Shouldn’t you also explain the thinking behind your explanation?) Where does it end?”

The thinking behind its answer was presented as follows:

Okay, let’s tackle this question about regression in explaining thinking. The user is asking if there’s a problem where each explanation needs another explanation, leading to an infinite loop. They also want to know where this chain ends.

First, I need to recall what an infinite regress is. In philosophy, it’s a situation where a proposition leads to an endless sequence of justifications. Like, if every belief needs another belief to justify it, you never reach a base. So applying that to explanations of thinking: if I explain my reasoning, do I then need to explain why I used that reasoning, and so on?

I remember foundationalism and coherentism as solutions to regress. Foundationalism says some beliefs are basic and don’t need justification. Coherentism relies on the consistency within a system. Pragmatism might say we stop when it’s useful. So maybe in explanations, we use similar stopping points.

Also, practical considerations. Humans can’t handle infinite explanations due to cognitive limits. Communication relies on shared assumptions. So in real life, people stop when the explanation is sufficient for understanding, even if not absolute.

Examples from other fields: math induction has a base case. Recursion in programming needs a base case to avoid infinite loops. So structured systems have mechanisms to halt regress.

Putting it all together: Theoretically, there’s a regression problem, but practically, we use foundational beliefs, coherence, or pragmatism to stop. The answer should mention the potential regress but explain how it’s managed.

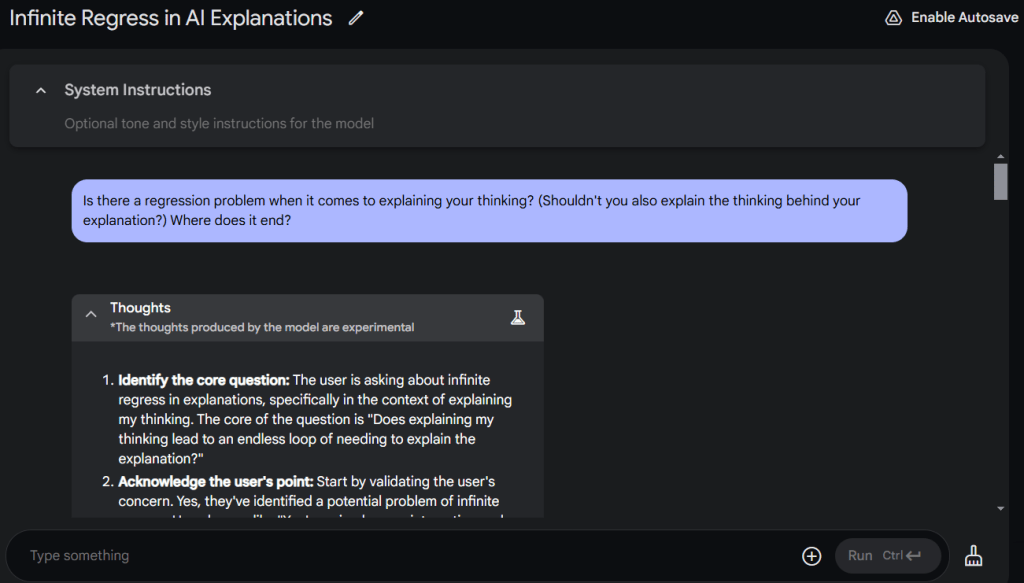

I asked Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental the same question:

Here’s Gemini’s thought process in full:

- Identify the core question: The user is asking about infinite regress in explanations, specifically in the context of explaining my thinking. The core of the question is “Does explaining my thinking lead to an endless loop of needing to explain the explanation?”

- Acknowledge the user’s point: Start by validating the user’s concern. Yes, they’ve identified a potential problem of infinite regress. Use phrases like “You’ve raised a very interesting and fundamental question…” or “This is a classic philosophical problem…”

- Define the “problem” (infinite regress): Briefly explain what infinite regress is in the context of explanations. Use clear and concise language. Example: “Infinite regress is the idea that every explanation requires another explanation, leading to an endless chain.”

- Apply it to AI explanations: Connect infinite regress to the specific scenario of AI explaining its thinking. Explain why this might seem like a problem for AI: AI operates based on algorithms, data, and processes – each of these could be explained further.

- Distinguish between theoretical and practical concerns: Crucially, separate the philosophical idea of infinite regress from the practical needs of explanation. Infinite regress is a theoretical construct, while real-world explanations have practical goals.

- Identify the goals of explanation: What are we trying to achieve when we ask an AI to explain its thinking? Think about the purposes:

- Understanding: To grasp how the AI reached its conclusion.

- Trust: To build confidence in the AI’s reasoning.

- Debugging/Improvement: To identify flaws and enhance the AI.

- Accountability: To understand why the AI made a specific decision (especially in sensitive contexts).

- Introduce the idea of “stopping points”: Since infinite regress is impractical, there must be points where explanation can stop. What determines these stopping points? Think about the context and the audience.

- Identify practical stopping criteria: Suggest factors that determine when an explanation is “good enough”:

- Audience: The level of detail needed depends on who’s asking (expert vs. layperson).

- Purpose: The goal of the explanation influences the necessary depth.

- Level of Detail (Granularity): Explanations can operate at different levels of abstraction (high-level overview vs. detailed step-by-step).

- Practical Limits: Resources and time are finite. Explanations can’t be infinitely long.

- Relevance: Focus on explaining the relevant parts of the process, not every single detail.

- Relate to AI specifically (again): Reiterate how these stopping criteria apply to AI explanations. Mention the underlying mechanisms (code, data, models) but emphasize that explanations usually focus on higher-level concepts that humans can understand.

- Conclude with a balanced perspective: Summarize by acknowledging the theoretical possibility of infinite regress but emphasizing that practical explanations are bounded and goal-oriented. Reiterate that the aim is effective communication and understanding, not philosophical perfection. Use a phrase that reinforces this, like “pragmatic and effective communication.”

Essentially, the thought process is about: Acknowledge -> Define Problem -> Contextualize -> Distinguish Theory/Practice -> Identify Goals -> Find Solutions/Stopping Points -> Apply to AI -> Conclude. This structured approach ensures all facets of the question are addressed in a logical and comprehensive way.

I found that these “thought processes” were sufficient as answers in themselves, so I won’t reproduce the actual answers here, too. And I think they are good, relevant, insightful responses. But I don’t feel I’ve gained much insight into either AI system’s actual “chain of thought”. And that’s perhaps because what I’m looking for doesn’t actually exist.

A simulated explanation is not a good explanation

When we seek to break open the black box, we want something that genuinely provides insight. But to my mind the chain of thought as it stands doesn’t even really try to do this: it offers a simulation of human reasoning, rather than a true explanation.

That’s because I know large language models like DeepSeek don’t reason like we do, even if they do a pretty good job of pretending to. Instead, to generate cogent sentences, they work probabilistically, using their training data to predict the word that is most likely to come next at any given point. This is why they are prone to error when you ask them to count letters, asking how many times the letter “s” occurs in the word “strawberry”, for example. They’ll confidently answer your question, simulating a likely human response, but will often fail to get the answer right.

Back in 1980, John Searle, a philosopher who does not speak or read a word of Chinese, illustrated this with the Chinese Room thought experiment. He invited us to imagine him being given a set of instructions on how to deal with a series of Chinese symbols. Simplistically speaking, the instructions dictate that when a certain set of characters is received, he is to produce a particular combination of squiggles in response. Following the instructions correctly results in what appears to be a coherent conversation in Chinese – but Searle, the person inside the “machine”, has no idea of the meaning behind his operations.

If we accept that something similar is going on when we “converse” with DeepSeek, then it’s no wonder any explanation feels phony to me. It’s because I’m asking for something it just can’t give. I’m perhaps demanding a “social explanation” (to use Mill’s terminology, discussed above), but demanding it of an entity that doesn’t really inhabit the same social world as me (or any social world at all).

In his open-access paper, Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences, Mill quotes Hilton as saying:

“Causal explanation is first and foremost a form of social interaction … The verb to explain is a three-place predicate: Someone explains something to someone. Causal explanation takes the form of conversation and is thus subject to the rules of conversation.”

Perhaps it’s that first “someone” that I’m feeling the absence of, in the DeepSeek version of explanation.

If all users understand that there is no “someone”, I don’t see anything wrong with using AI tools like DeepSeek. And I know that this form of explanation is genuinely useful, not only in discerning how these systems come to the answers they do, and thus screening for bias and error, but also in helping the systems themselves to check for accuracy at each step that is made explicit. It will undoubtedly be a growing phenomenon as explainable AI becomes more widespread. But to me, it feels as if the “chain of thought” is a deliberate deception, asking us to play along with a form of reasoning that isn’t actually taking place. It’s why I don’t feel satisfied with this kind of simulated explanation – I feel I want something that REALLY explains, and doesn’t just pretend to.

Related links

There’s lots of interesting reading on topics related to AI and explanation.

- DeepThinking To Some Purpose, published in the Daily Nous, is the article that inspired this post.

- No One Truly Knows How AI Systems Work. A New Discovery Could Change That is a Time article that deals well with the black box problem in AI (with interesting news on a way in which we might be able to get a different kind of explanation)

- Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences by Tim Miller is a really interesting open-access article on the different types of explanation and how they relate to AI

- Forms of explanation and why they may matter by Jonathan Baron explores the difference between psychological and neuroscientific explanations

- DeepSeek Has More To Offer Beyond Efficiency: Explainable AI is a Forbes article on DeepSeek’s transparent approach

- Revolutionizing AI Reasoning with Self-Prompted Chain-of-Thought (SP-CoT) describes how chain-of-thought reasoning helps AI systems to be more accessible and reliable

- Why LLMs Struggle to Count Letters in Words is a good explanation of the tangles that large language models can get into when you ask them how many instances of a particular letter occur in a particular word

General introductions from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

What do you think?

This blog has been an exercise in feeling my way through my intuitions, to see if I can make better sense of them. I’m not sure I’ve fully achieved that yet, and would appreciate it if my brain would issue its own chain-of-thought explanation to make things a bit clearer. Failing that, I’d love to have your input. What are your thoughts on DeepSeek’s chain-of-thought explanations?

Leave a comment